Lighting designer Steve Lieberman talks Coachella and the rave days

By Christopher Barker | Semipermanent

April 2, 2019

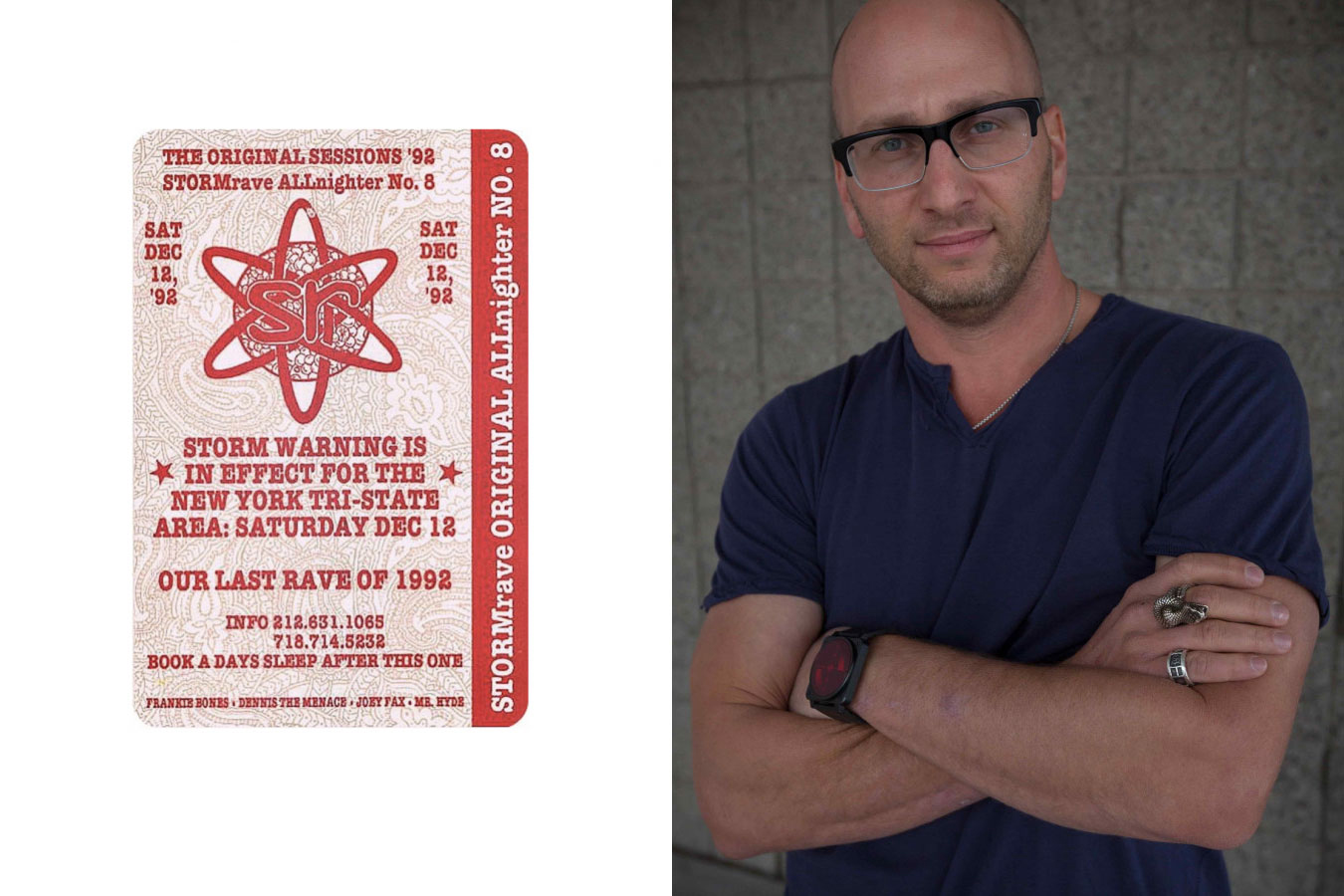

Steve Lieberman started going to warehouse raves in a mid-80s New York and hasn’t really stopped since. A few decades and technical upgrades later, his production/lighting company SJ Lighting is making sensory magic on an industrial scale, where iridescent beams and crushing strobe lights provide a lightning strike to the cortex of thousands worldwide.

We traced his journey just before he jumps behind a lighting booth at the world's most influential festival.Interview: Christopher Barker

I want to start by asking you about the Storm Raves in New York City in the 80s. Was that your first exposure to club culture?

Wow, that's a name I haven't heard in forever. But yes, you’re taking me back to the very beginning of my exposure to the rave scene.

I recall the first rave I ever went very distinctly. One of my best friends called and said 'I found a party, you're going to love it'. I was like 'okay, sure'. We drove to this record store in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn and bought a ticket to the party, which included a four-by-four inch square piece of paper with photocopied, hand-drawn directions to the venue. We drove around for some time until we ended up in the parking lot of a supermarket, and started walking around the back in this derelict marsh/abandoned warehouse area I remember seeing a flag. It was the Storm Rave flag flying in the air which I'd never seen before. I didn't even know what the Storm Rave was. Then there were five metal detectors lined up with a really large human being in front of them. I remember walking into this giant warehouse with hard techno blasting and people jumping up and down. And that was it.

Did it click for you instantly? Like 'this is something I'm going to be a part of forever?'

It was unassuming and very subconscious. Part of the reason I'm still in this industry today is because it's always been fascinating. I've never broken it down like 'wow the sociology of my life is so intriguing'. I just had my head on a swivel thinking 'this place is amazing and I want to be a part of it'. There was really no adjective to describe what was going on, it was just 'this place is crazy. When are we coming back?'

Many of the other famous parties in New York — The Loft, The Garage, Zanzibar to name a few — were very much sound-system oriented. At what point did the visual side of things click for you?

It wasn't anywhere like it is today. That first party had maybe four or six lights plugged into wherever you could find electricity. There was no overall visual design. And that was an evolution I didn't start seeing until around six or seven years later, which was part and parcel with club culture itself moving forward. That was when the Club Kid subculture grew exponentially and the technology moved to support those events. The customer becomes more educated, and then the manufacturers and designers start understanding that there's a marketplace amongst this culture that embraces technologies, environments and design ideas.

It's interesting you mentioned Club Kids. Disco 3000 was more visual than sound.

I wouldn't consider myself a Club Kid, but while working in those nightclubs I was doing a lot of those events. I didn't put angel wings on or anything like that.

Marquee, Las Vegas

So in that mid-90s time-period you weren't the first person to do club lighting, but certainly amongst the first generation. Did you feel like you were writing the rules as you went along?

That's exactly what I was doing because I didn't know of anybody else doing it and I knew I wanted to leave more of a legacy through design. Straight out of college I had a job building clubs and shows. Even then I was asking my boss if I could design stuff. I'm not formally trained in any of this, I just designed what I felt was right and that has translated into a viable business in programming and design some 20 years later.

Where were your design references coming from?

I get a lot of influence from architects rather than lighting designers, mainly because of the influence of permanent structures throughout history. Zaha Hadid, God rest her soul, is one of the most creative people since the dawn of design. Her stuff is fascinating to me, but I also like the retro-futurism of American architects like John Lautner. Of course, there is a plethora of visual influences, but most of my design aesthetic and philosophies came from architecture.

Drais, Las Vegas

There's also been a resurgence of artists using light as a medium; James Turrell comes to mind. Do you take a fine-arts look at it too?

I'm a huge, huge fan of James Turrell. We had an opportunity to do some lighting design for the Sheats-Goldstein residence, which is a John Lautner house. James had done work on that property and has an installation there which is just amazing. His design aesthetics are very moving because of their clean details, like knifes-edge finishes on a wall so the perspective feels like it's falling instead of seeing a 90-degree turn. His work at Roden's Crater is amazing too. A fantastic artist.

I feel that you share a mission for immersion in your work. Can you talk about creating immersion with light?

I'm not sure I can put my finger on it exactly. I just know I don't want a show to feel like it's front-loaded; that you can turn around and escape it.

The nice part of working in entertainment is that people come to these places to escape the every day. So how do you give them this portal out of their normal everyday life? My design philosophy and protocol is to just put myself in the space and ask ‘what's going to feel good?’ Is it organic? Is it geometric? Who is performing? What's the name of the club? The city? These parameters change for every project and there's no one broad stroke answer. Everyone's unique, everybody's different, so you have to approach it with that in mind.

The lighting desk at Marquee, Las Vegas

Coachella is coming up. You've done the stage design and lighting for the Yuma tent since its inception — what's that incremental process like?

It's a new design every year. I'm planning for myself as a neurotic, obsessive-compulsive design-oriented person. Even if designs don't make it into the field, I don't recycle them elsewhere. The same thing applies for the Yuma Tent.

The Yuma Tent's music policy is deep, dark techno but it depends on who is performing. Last year, we had Fisher performing. He's a great character insofar that his personality being very bright. So for him, while it won't be bright lights, it's not going to be as dark as someone like Danny Tenaglia. Chris Liebing, for example, likes it dark and minimal, so we keep it dark on stage. I want to make sure the artists personalities and the music they're playing are reflected in the production.

Yuma Tent, Coachella

There are certain parameters that don't change but we try and give the audience a new perspective — perhaps the form factor or the environment. One of the main priorities of Golden Voice (who produce Coachella) is that there is no truss or structures hanging in there. It needs to be a very dark, clean, minimal space. So I have to know how the fixtures are hung on the beams of the structure with black-liner to minimise the visual impact. Last year, we designed a custom metal structure that we hung on the backwall. This year we have a really cool feature I don't want to talk about until after the show, but it's a very dimensional so you won't notice when it's off, but when it's on it will be this floating detail that's all mapped and very clean.

I've run my own parties in the past, and I find it's really difficult to design a collective experience that goes exactly the way you want it to. Sometime's things don't work but everyone has a great time, and other times you do everything right and the party falls flat. Do you think you can design for really positive social cohesion in a space?

I don't know that anyone will ever get this utopian euphoric design experience 100% of the time, but we're always trying to improve the experience. If we get it to 80%, that's a pretty great experience. As a philosophy, I think we design the experience we'd like to be a part of, but there's always environmental conditions that might change things, and those are just the variables we deal with on a daily basis.

Yuma Tent, Coachella

And humans aren't predictable either.

It doesn't mean you didn't design an amazing experience for them. There's always going to be some variable you need to adapt to and overcome. That's part of the experience.

Going back to our earlier conversation, Boiler Room recently put on a Storm Rave reunion party with Frankie Bones. Do you think we're heading into a bit of a renaissance of lo-fi, warehouse production?

It puts a smile on my face that in the past two or three years that sound seems to be growing in popularity, because that's what we were listening to 25-years ago. There are so many genres of music now, I don't even know what they're talking about. I just know what I like: good vocals, drums and dark beats.

I don't know that the production is going to minimise because the value has increased so much, not just to the consumer but to the artists as well. As a business we spend a lot of time with producers making the shows they want to make as a brand promise to their audience.

Tell me more about the Sheats-Goldstein house, it's endowed to LACMA, right?

Correct.

How did you fall into a job like that?

We designed a nightclub in Miami many years ago called LIV. Right after we finished it, we got a random call from an architect in L.A named Duncan Nicholson. He called me and wanted to speak to the lighting designer for LIV, so I said 'you're talking to him'. ‘Fantastic’ he says. 'I have a client, I can't tell you who, but he loves your work and would like you come and check this job site out'.

Club James, Sheats-Goldstein Residence, Los Angeles

Obviously I'm intrigued, so I say yes and he gives me the address for the Sheats-Goldstein residence, which I didn't know about until I drove down the driveway and thought 'you've got to be kidding'. The club didn't exist at that point, it was just a hole in the ground.

So I meet Duncan who introduced me to James (Goldstein), and he and I hit it off and I've been working there for ten years now. Duncan was the last disciple or understudy of John Lautner before he died. Sadly he passed away around four years ago, but Conner + Perry Architects handle the house now and we keep their names alive.

Club James, Sheats-Goldstein Residence, Los Angeles

I've heard there are good parties there too.

Amazing parties. The club is called 'Club James' and above it is a tennis court. They're putting in a swimming pool next to it, next to the one that has windows into his bedroom. We handle all the technical services for the club like the lighting and lasers. Jim wanted a laser door so we built a custom door with laser beams that, when you walk through it, it shuts off before turning back on again. Its a very clean aesthetic but it is very cool.

So the overall theme of the property is very much John Lautner — this steel, concrete obtuse design aesthetic. If you ever have the opportunity to visit it's very much worth your time.